A Retelling of the Places Spirits Built: The Origin of The Osun Osogbo Grove

Akosejaye which translates as ‘the first step or feet in life’ was how Yorubas got a glimpse of their newborn’s destiny. Like many cultures across the continent, the Yorubas believe that every newborn arrives in the world with ipin– destiny. On the third of a baby’s arrival, divination is done to ascertain the baby’s destiny on earth. Details about his purpose and likely obstacles are shared with the parents. In a time when akoseyaje was the norm, Yoruba deities were considered the shapers of destinies. They influenced the paths of individuals and guided them all the way.

If the deities were revered as the architects of destinies, how did they also build literal towns? Yoruba spirituality involved worshipping deities in exchange for the protection and establishment of their towns. Many Yoruba communities had reciprocal relationships with certain deities where offerings and rituals were performed to honour the deities and seek their favour in return for blessings, protection and prosperity. The people of Oyo regarded Ogun, the god of iron, as a crucial force in the founding of their town. Associated with the clearing of forests and the establishment of settlements, the people worshipped Ogun in exchange for prosperity and protection.

According to Yoruba mythology, Osun became the prominent deity of the people of Osogbo after Olutimehin, a renowned hunter led a group of people to settle on the bank of the Osun river. An account by UNESCO World Heritage says that Olutimehin convinced Larooye, the king, to settle with his people in the Osun forest. Larooye, on behalf of the people, made a pact with Osun to worship and protect the forest if only Osun would protect and establish them. Osun bestowed growth on them and the people multiplied and had to move out of the grove. They settled in neighboring places but the grove remained sacred. Like they did when they lived in the grove, the people often returned to the grove to worship. The grove was revered and intact until colonial infiltration.

The Osun Osogbo Sacred Grove suffered degradation during the colonial period. Obas began to lose their political relevance and territories. Colonial authorities sought to encroach on land and resources and the grove was not immune. Soon, its shrines were looted and its natural resources were exploited. Its devotees abandoned the grove and its spiritual significance diminished. This was the state of the grove in the 1950s.

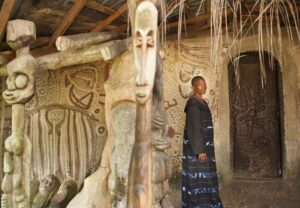

The Grove began to regain its dignity after the Oba of Osogbo and Susan Wenger, an Austrian artist who settled in Osogbo joined efforts to revive the grove. Susan Wenger, also known as Adunni Olorisha, took an interest in the shrines dedicated to Orishas. She collaborated with traditional artists to erect sculptures that symbolize the sacredness of the grove. The grove was completely revived and there are more than 40 powerful sculptures and sculptural architectures within it (UNESCO World Heritage).

The grove is a 75-hectare dense forest nestled along the banks of the Osun River. Founded some 400 years ago, the grove is the largest sacred grove that has survived. Today, the Osun Osogbo Sacred Grove is home to 40 shrines, sculptures, and works of art dedicated to Osun and other deities. The UNESCO World Heritage reaffirms that the grove contains 400 species of plants of which more than 200 species are known for their medicinal uses.

The annual Osun Osogbo festival is a processional festival where the people reenact the pact Larooye made with the deity.

The Osun Osogbo Sacred Grove is a symbol of the people’s reverence for nature. While it can be argued that the origin of sacred groves in Yorubaland was shrouded in mythology, we cannot overlook the resulting ecological conservation. Inadvertently, we have a people who understood their place in the cosmos and sought to preserve the natural order.